| Incident: | A landmine exploded, killing four children between the ages of 9 and 13 |

| Date: | April 6, 2024 |

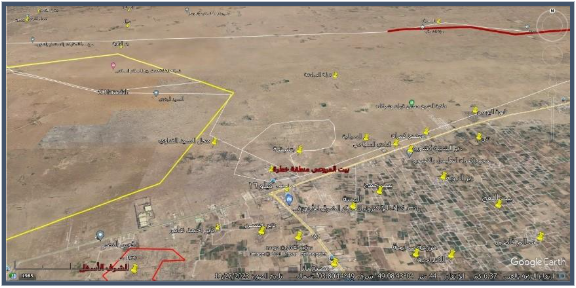

| Location: | Al-Qaz’ah neighborhood in Al-Qatie city, in Al-Maraw’ah district |

| Type of Violation: | Landmines planted everywhere continue to claim the lives of men, women, and children |

For years, residents of the Hodiedah coast have been living an ongoing tragedy as their lands have been transformed into killing fields. Landmines planted everywhere continue to claim the lives of men, women, and children. On Saturday, April 6, 2024, residents of the Al-Qaz’ah neighborhood in Al-Qatie city, in Al-Maraw’ah district, a landmine exploded, killing four children between the ages of 9 and 13.

Reports on the incident varied slightly. While the Yemeni Landmine Observatory reported that a “warhead” exploded on four children, leaving their thin bodies shattered and covered in shrapnel, human rights activist Mujahid al-Qub said the victims were three children, one of whom, aged 13, died due to the explosion. Another 10-year-old boy’s left leg was amputated, and he was also wounded by shrapnel in various parts of his body. The third child, aged 13, was seriously injured when shrapnel penetrated his head and chest. He noted that the victims were returning from a well where they went to fetch water.

Media outlets covering the story disagreed over who was responsible for this crime. Although the Yemeni Mine Observatory, which most of the coverage relied on as a source, did not accuse any party, merely stating that the explosion was caused by “an unexploded ordnance,” the Suhail Net website blamed the Houthi group, saying the object was “one of its remnants,” the pro-Houthi Yemen Today channel blamed the Arab Coalition, saying it was one of its remnants. This is not the first time each side has held the other responsible. This exchange of accusations is perhaps more dangerous than the crime itself, as it involves a futile debate in which victims are reduced to mere numbers that are quickly forgotten, while the horror of the buried landmines remains, lurking for its next civilian victims.

Background:

Yemen has suffered from landmines since the outbreak of political and military conflicts in the 1960s, through the wars in the central regions, the events of 1994, and beyond. In 1998, Yemen ratified the Ottawa Convention, also referred to as the “Mine Ban Treaty,” on Prohibiting the use, Stockpiling, Production, and Transfer of Anti-personnel Landmines, requiring the government to destroy its stockpile of landmines within 10 years.

According to the Yemeni National Mine Action Center, following the ratification of the Ottawa Convention, Yemen had destroyed its stockpile of mines by 2007, thus coming close to being declared mine-free. However, due to the unrest that began three years later, followed by the conflict between the legitimate government and the Houthi group after the latter’s coup and violent takeover of the capital, opening battlefronts across much of Yemen, and a renewed boom in mine-laying, particularly by the Houthi group, the Yemeni government submitted four requests to postpone its obligations under Article 5 of the Convention. The last extension was granted until March 2028.

Since the outbreak of the war in September 2014 until the truce was declared in April 2022, the Houthi group laid landmines in combat zones in many governorates, and marine mines in the Red Sea. Unfortunately, no clear maps of the minefields, making future demining efforts extremely difficult. Yemen is now one of the most heavily mined countries. Just two days before the mine explosion that killed the children of Al-Maraw’a in Hodeidah, the world was celebrating International Mine Awareness Day. On this occasion, the US Embassy in Yemen tweeted on its X account that “the Houthi group had turned Yemen into the largest minefield ever.” Amin Al-Aqili, director of the National Mine Action Program, said in a previous press statement that “the program and partners have removed more than 1.25 million mines and explosive devices from 2015 to April 2024.”

Children are the most vulnerable victims:

The Houthi group has resorted to several tricks in manufacturing mines in various forms to trap the largest number of victims. Al-Araby Al-Jadeed newspaper quoted a resident of Al-Khokha District in Hodeidah Governorate as saying that dozens of mines are hidden in the trunks of damaged palm trees thrown along the roadside, and inside plastic boxes. The newspaper quoted its sources as saying that the Houthi group has rigged farms and side roads in all areas of the southern Hodeidah countryside with anti-personnel mines, which have left civilian casualties, including shepherds. The residents have repeatedly seen livestock and dogs being blown to pieces in broad daylight after running over anti-personnel mines.

The newspaper also quoted experts as saying that several landmines and explosive devices removed in Hodeidah were operated by infrared, exploding as soon as any object, even a child, passed through their lens. This has forced residents to abandon their towns in the southern Hodeidah countryside for years.

A report by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in November 2022 stated that the number of civilians killed or injured by explosive ordnance remnants of war in Yemen has increased by 20 percent since the start of the truce in April 2022, compared to the prior six months. Data from Save the Children revealed that the period between 2018 and 2022 witnessed an alarming increase in the number of child victims of landmines and unexploded ordnance, from one child every five days to one child every two days. A report issued by the American Center for Justice documented several cases of killing, injury, and destruction of private objects caused by mines that the Houthi group has laid in 17 Yemeni governorates, where war took place between June 2014 and February 2022. The report stated that (2,526) civilians were killed, including (429) children and (217) women, and (3,286) others were injured, including (723) children and (220) women. It also stated that 75% of those injured by mines suffered permanent disabilities or lifelong disfigurement.

The report also shows that children are more vulnerable to the dangers of these mines and munitions than adults, constituting more than half of the victims in Yemen. Approximately 20% of child casualties in the Yemeni war were the result of mine and unexploded ordnance accidents. The governorates of Hodeidah, Taiz, and Sa’da recorded the highest number of these incidents, according to data from the Justice Yemen Pact for Justice Coalition, a coalition of 10 human rights organizations and centers monitoring the human rights situation in Yemen. Yemen has witnessed serious violations due to the war between the Houthi group and the internationally recognized government.

Who is responsible?

The Houthi group accuses the Arab coalition of being behind unexploded ordnance that has killed or injured hundreds of people, many of whom have suffered various disabilities. However, according to data from the Justice Charter for Yemen Coalition, the Houthi group “is responsible for approximately 72 percent of landmine explosions across Yemen, while the remaining percentage is distributed among unknown or outlawed groups.”

A report by the New York Times concluded that the Houthis planted most of the landmines and other buried explosive devices in Yemen, while a report issued by the Washington Institute addressed the massive scale of landmine use by the Houthis. According to several reports, it is difficult to locate these mines, especially anti-personnel, and anti-vehicle mines, due to their indiscriminate planting and lack of minefield maps.

The continued control of the Houthi group over many areas in Yemen also poses another challenge to demining efforts. Other challenges facing the demining operations in Yemen include the lack of minefield maps, the type of mines planted, and the lack of qualified local demining teams. Among the technical challenges is the government’s lack of modern equipment to detect these devices and explosives. Furthermore, the fact that floods sweep some mines from one area to another complicates locating them.

Conclusion:

The Yemeni mines tragedy, which began a decade ago and has not yet ceased, is greater than all reports and statistics indicate. There are no indications that the bloodshed of the innocents and the torrent of tears streaming from their eyes are anywhere near stopping. Therefore, there must be a solution based on adherence to the Ottawa Convention, particularly Article 4, which stipulates the removal, disposal, or destruction of explosive remnants of war. This requires each party to the conflict to be responsible for the territories under its control. Consequently, minefield maps must be provided. Comprehensive mine risk education must also be conducted immediately after the war ends, providing residents of areas affected by explosive remnants of war with the necessary information and educating them about the dangers.

Unfortunately, current local, regional, and international efforts are insufficient to eliminate landmines soon. The Yemeni government’s efforts are weak due to the fragility of its institutions. Therefore, joint coordination between the Yemeni government and regional and international donor agencies in this field, to appoint a single entity responsible for identifying cleared areas and those still at risk of mines, will yield more effective results.

Landmines will remain a threat to the lives of Yemenis in the post-war phase, requiring urgent intervention by the UN envoy and his team to discuss minefield maps in the conflict zones, the border areas with Saudi Arabia, and Yemen’s Red Sea coast. Also, support the National Mine Action Center’s projects and train local and international demining teams. An independent body should also be established to raise awareness of the dangers of landmines, a practical plan should be developed for the post-war period, and a special fund should be established to care for mine victims.